- Home

- News

- What’s On

- Activities for Children

- Arts & Crafts

- Autos and Bikes

- Business events

- Car Boot & Auctions

- Charity events

- Churches & Religious

- Comedy

- Dance

- Days out & Local interest

- Education

- Exhibition

- Film

- Gardening & Horticulture

- Health

- Markets & Fairs

- Music

- Nature & Environment

- Spiritual

- Sport

- Talks and Discussions

- Theatre and Drama

- Business

- Local Information

- Jobs

- Deaths

- Charity events

- Contact Us

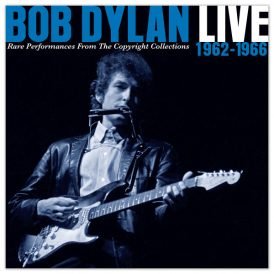

Robin Hood, Will Scarlet… and Bob Dylan

Ex Macclesfield Express editor and local historian Doug Pickford does a little digging into connections between Macclesfield and Bob Dylan.

It is a long and winding road that lies between iconic folk singer Bob Dylan and Macclesfield, but when there’s a twist by way of a poisoning, Robin Hood and an evil ghost, that highway turns out to be never-ending.

Some aficionados of the Nobel prizewinning minstrel, who epitomised the music of a hippy generation, think one of his most influential songs was partly based on an old folk tune that is rooted in an ancient ballad concerning a nobleman who owned both Treacle Town and nearby Leek and whose ghost was responsible for the foundation of a Cistercian monastery – the ruins of which are just a mile away.

This monastery owned most of Monks Heath, hence the name, plus Macc Forest and Alderley

Following debut album in 1962, which mainly involved traditional folk songs, Dylan made his breakthrough as a songwriter with the release of a 1963 album featuring “Blowin’ in the Wind” and A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall, both now classics

It’s a pound to a penny that the superstar had not heard of Dieulacres Abbey, or maybe even Macclesfield, before he wrote and sung “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall”, but he was aware of traditional folk songs that had been passed on all the way down the centuries; and many fans and scholars have subsequently pointed out “A Hard Rain’s” local connections – so it’s a fair bet that word has trickled through to him by now. Not that he has ever been noted for saying much.

On September 22, 1962, Dylan appeared for the first time at Carnegie Hall where his three-song set marked the first public performance of “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall,” a complex and powerful song built upon the question-and-answer refrain pattern of the traditional British ballad “Lord Randall“.

One of the oldest traditional ballads in the English language, it is thought that the Lord Randal in the ballad might be Randolph, 6th Earl of Chester who died in 1232. He was poisoned. Randolph was also known as Ranulf and was a guest at the house of William Peverel the Younger, his host attempting to kill him with poisoned wine. Three of his men who had drunk the wine died, while Ranulf suffered agonising pain.

A few months later Henry became king and exiled Peverel from England as punishment. Ranulf succumbed to the poison on 16 December 1153.

The ballad is known all over the world, sometimes under different titles. One variant in England is “Henry my son”, but the form is always of a man who has been poisoned bequeathing his goods to his relatives. To his “true-love” he gave the means for retribution

Ranulf’s grandson died at Wallingford on 26 October 1232 aged 60. His internal organs were buried at Wallingford Castle, his heart at Dieulacres Abbey close to Leek, which he had founded, and the remainder of his body at St Werburg’s in Chester.

It has also been suggested by folk-song expert Anne Gilchrist In The Journal of Folk Song Society (Vol. ii., No. 6 and Vol. iii., No. 10) and others that the activities of Ranulf, Earl of Chester form the basis of the ballad “Lord Randal” which contains the lines “I fear you are poisoned, Lord Randall, my son.” The legend goes on to say that Ranulf went to Hell, escaped, visited his grandson and founded an abbey renowned for murder and mayhem.

According to this legend the earl was visited on his death-bed by demons to accuse him of his sins and he was condemned to Hell but because of the incessant howling of the dogs while he was there the Prince of Hell ordered that the Earl should be expelled from their confines, “for no greater enemy of theirs than Earl Randle had ever entered the infernal dominions.”

Ranulf still wasn’t finished and the story goes on to say he appeared to his grandson in a vision, and commanded him to found a Cistercian abbey near Leek at a place called ‘Cholpesdale’ on the site of the former chapel of St. Mary the Virgin.

When the young grandson, also Ranulph, told his new wife Clemence about his vision of his grandfather and the proposed foundation she exclaimed in French: ‘Deux encres!’ — ‘May God grant it increase!’ Hence the name of the place – Dieulacres.

The abbey soon gained a distressing notoriety for the abbot retained an ‘armed band’ and his power over the area was absolute.

He is said to have erected gallows and was legally able to hang anyone he pleased.

A royal commission in 1379 noted that the Abbot of Dieulacres, in order to control the area, had used his armed men to do all the roguery they possibly could and that they ‘have lain in wait for them, assaulted, maimed, and killed some, and driven others from place to place…”

In 1380 the abbot was arrested and imprisoned following an incident during which a John de Wharton was beheaded on the orders of the abbot. It was not a very long time before he was pardoned and released.

In subsequent years some were accused of theft and the abbot was criticised for appearing to protect them. There were also numerous lawsuits.

Upon the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the abbey was surrendered in 1538. Local tradition and folklore would have it that it put an end to 400 years of mayhem brought about (supposedly) by the evil spirit of Ranulf.

Langland’s “Vision of Piers the Ploughman” has a reference which may be to this ballad when a character says “I ken rymes of Robin Hode and Randolf Earl of Chester”.

The ballad that connects the earl with Robin Hood makes reference to Will Scarlet being born in Macclesfield, and he meets Robin in the nearby forest – either Leek Forest or Macclesfield Forest, both connected, and both spreading, over to Sherwood Forest.

This area was once a dense mass of trees. At the time of the Norman Conquest and before, the Forest of Lyme (Lyme denoting boundary or limit) was a vast tract from Ashton under Lyne in the north, down to Lyme Park, Lyme Green, Newcastle under Lyme and Audlem (Old Lyme).

It was the eastern boundary of the Cheshire earldom and later parts of it became the forests of Leek and Macclesfield. It was here that the Davenport family took charge as holders of the right to kill or maim poachers at will. And it was here that the spirits of the forest became real-life people such as Robin and Will and Little John, just as in other areas.

Will and Robin and Little John are the folk memories of that which may or may not have been, but what was wished and hoped for. They were the saviours of the common people, their champions, the righters of wrongs and the fighters against officialdom. The forests – like both Macclesfield and Leek – were places where the commoners could not go because the higher ranks kept the deer and the boar for themselves – to hunt and to eat. Trespass or poach and you faced death. But through the supposed escapades of Robin and his men it was possible to cock a snook at these earls and dukes who came perhaps once a year to the area to hunt and cavort. It was possible to be part of the forest through the spirit of the forest.

Robin, Will and John were each and everyone. They were (and are) the free spirit within us all and while Hollywood wants them to he romantic figures, our hearts want them to be what they always have been.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login